The Worst Places to Live — Anti-Ranking of Countries

We often hear about which countries are the best to live in and why. Numerous rankings of quality of life and human development index scores regularly reinforce this narrative.

However, there is also another side of the story: the world’s worst countries to live in which rarely make headlines. These rankings are hardly objective either: they tend to focus primarily on nations embroiled in military conflicts, overlooking the fact that there are peaceful countries where people survive rather than live.

That’s why we’ve compiled our own ranking, based on factors that truly matter to people: healthcare, crime rates, access to drinking water, and more.

The World’s Worst Countries to Live In

As of 2025, global rankings often mention Libya, Syria, and Venezuela as the most unfavorable places to live. Their position in these lists stems from political instability that has escalated into mass protests or prolonged civil wars. However, we excluded them from our ranking, as there are countries with conditions even more dire.

Yemen (Middle East)

While much of the Middle East flourishes on energy exports and economic diversification, Yemen consistently appears in the news for all the wrong reasons. It remains one of the hardest places on Earth to live.

Since 2014, Yemen has been torn apart by a civil war between the internationally recognized government and various radical factions, the most powerful being the Houthis. According to the United Nations, the conflict has claimed around 377,000 lives, while over 21 million people, roughly two-thirds of the population, are in need of humanitarian aid.

The country shows the classic symptoms of a failed state: government institutions have collapsed, the police and courts no longer function, and vast regions are controlled by tribal and religious militias.

Yemen’s GDP per capita is around $820, inflation exceeds 30%, and about 80% of Yemenis live below the poverty line. Many lack access not only to electricity but even to food, as neighboring Saudi Arabia and Oman have blocked most imports. Against this backdrop, the national currency has devalued several times, making even basic goods unaffordable for the majority of families.

Around 600,000 children suffer from acute malnutrition, including 120,000 in severe form, where survival is measured in days.

Access to drinking water is another major problem; only about one-third of Yemen’s population has it. Sanitation and sewage systems have been destroyed or are no longer maintained. Only half of the country’s medical facilities remain operational, and even those face severe shortages of medicine, fuel, and staff. These two factors have created ideal conditions for the spread of cholera.

In 2024 alone, nearly 250,000 cases of cholera were recorded, leading to over 860 deaths, 35% of all global cholera outbreaks. In addition, Yemen remains a natural hotspot for malaria, typhoid fever, schistosomiasis, and leishmaniasis.

Electricity is available to about three-quarters of the population, but supply is unstable — blackouts are frequent and can last for weeks. Internet access is minimal.

In such conditions, maintaining law and order is nearly impossible. Yemen has become a battleground for multiple armed groups, each with its own interpretation of justice. As a result, crime rates continue to rise, alongside kidnappings, extortion, and the killings of journalists.

Haiti (Central America / Caribbean)

The Caribbean is often marketed as a «tropical paradise.» Indeed, destinations like the Dominican Republic, Barbados, and the Bahamas attract millions of tourists each year, driving economic growth and improving local living standards and Human Development Index scores.

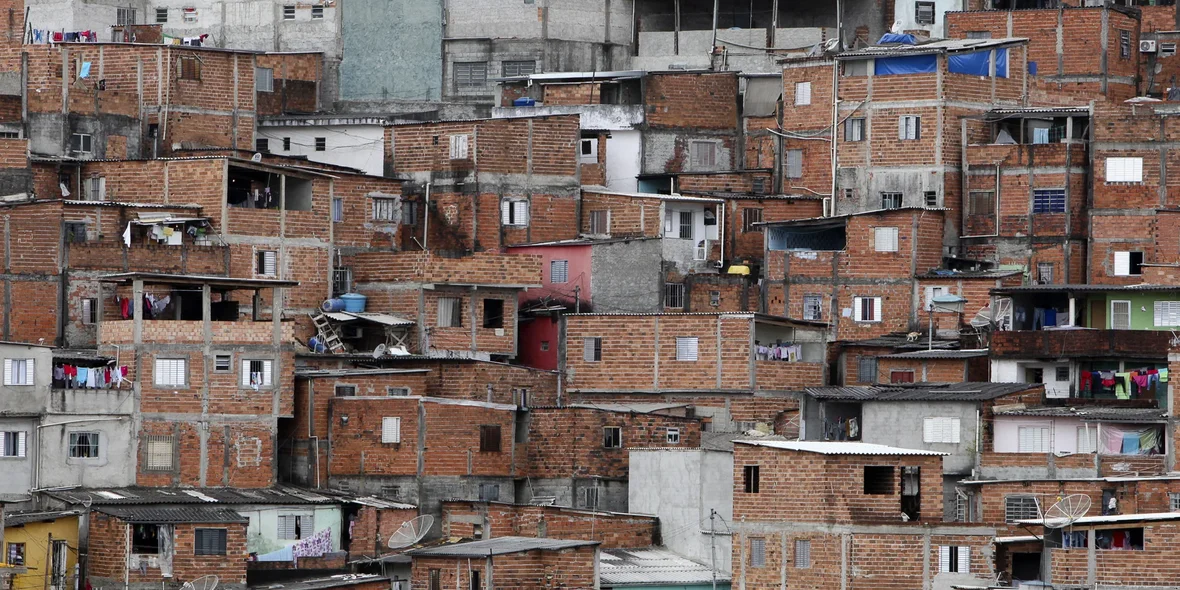

However, there is one country in the region where this idyllic image collapses entirely — Haiti. The assassination of the sitting president plunged the nation into chaos, leaving it effectively ungoverned. By 2025, roughly 85% of the capital, Port-au-Prince, is controlled by various armed gangs, none of which are interested in maintaining order.

Over the past three years, more than 40% of all deaths in parts of Port-au-Prince have been violent, triggering one of the largest internal displacements in modern Haitian history; an estimated 1.3 to 1.4 million people have fled the capital region for the countryside.

Because gangs control major roads, fuel supplies, ports, and humanitarian corridors, Haiti faces a severe food shortage. Acute food insecurity affects around 50% of the entire population of about 5 to 6 million people.

The healthcare system is on the brink of collapse. Access to basic medical services is extremely limited, as many clinics are either closed or unsafe to reach. Only 18.9% of Haitians have access to safe drinking water, forcing the majority to rely on rainwater or contaminated river sources, a situation that has led to frequent outbreaks of tuberculosis and cholera.

Haiti’s instability has deep roots. It began in 1986, when dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier was overthrown. Since then, the country has seen over 20 governments, most of which failed to complete their mandates. Local elections are regularly disrupted, and power changes hands through military coups or mass protests that precede them.

Adding to the country’s misery are frequent and powerful earthquakes — with magnitudes reaching 7.5 — and regular hurricanes that devastate an already impoverished nation.

Madagascar (Africa / Oceania)

Madagascar is often portrayed in popular culture as an exotic tropical island, yet the reality of life there is far from idyllic. Since gaining independence in 1960, the country has effectively functioned as a raw-material appendage of Europe, with successive governments prioritizing foreign interests over those of their own people. This legacy continues to shape Madagascar’s severe socio-economic problems — problems that every new president has so far failed to resolve.

The economy is heavily dependent on agriculture, primarily the export of vanilla and cloves, while mining operations supply nickel and cobalt to global markets. However, decades of political instability, corruption, mismanagement of state resources, and the absence of an industrial policy have left Madagascar among the world’s poorest nations. As of 2025, approximately 75% of the population lives below the poverty line, and over half of them — in extreme poverty. More than 40% of children suffer from chronic malnutrition.

The healthcare system is severely underdeveloped — on average, there is one doctor for every 10,000 residents. Each year, the country records over 1.6 million cases of malaria. Additionally, bubonic plague outbreaks occur almost annually, as Madagascar is home to natural reservoirs of the disease — rodents and insects. While plague epidemics primarily affect rural areas, they have also reached major cities, as seen in the 2017 outbreak.

Access to safe drinking water is another major issue: only about 36% of the population has it, and even that water is often contaminated. As a result, many residents contract schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease caused by larvae that penetrate human skin. The country also harbors several endemic infections to which foreign visitors have no natural immunity. Overall, up to 70% of the population is at risk of contracting some form of infectious or parasitic disease.

Madagascar also ranks among the ten countries most vulnerable to climate disasters. Every year, it is hit by three to five tropical cyclones, while the southern regions suffer from severe droughts. Rounding out the list of local hazards are frequent shark attacks along coastal areas and crocodile attacks in rivers and ponds.

East Timor (Oceania / Asia)

East Timor (officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste) is one of the world’s youngest nations, having gained independence only in 2002. Prior to that, it was a Portuguese colony, and following the fall of Portugal’s Salazar regime, independence movements began to take shape. While Western Timor, a former Dutch colony, opted for integration with Indonesia, the eastern half of the island took a different path, one that led to war. The conflict was hopelessly unequal: Indonesia invaded and occupied East Timor for 24 years, carrying out widespread repression and indiscriminate killings of civilians and combatants alike.

When Indonesian troops finally withdrew under UN pressure, they employed a scorched-earth policy, destroying roughly 70% of the country’s infrastructure, including schools, hospitals, and public utilities. Since then, weak infrastructure, chronic poverty, lack of industry, and frequent natural disasters have turned daily life for most citizens into a struggle for survival.

Today, about 42% of the population lives below the national poverty line, while youth unemployment exceeds 30%. Most people engage in subsistence farming or small-scale export agriculture. However, yields are unstable and heavily dependent on monsoon rains, as every strong tropical storm triggers devastating landslides.

The healthcare system is among the weakest in Asia, with only 2.4 doctors per 10,000 inhabitants. As a result, around 40% of settlements lack even basic medical posts. Life expectancy remains low, barely reaching 59 years.

These conditions foster the spread of infectious and parasitic diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and intestinal infections. Since 2022, East Timor has also faced recurring dengue fever outbreaks, while vaccination coverage remains below 70%. Chronic malnutrition further exacerbates the crisis: about 46% of children under five suffer from it, and 11% are severely emaciated. Nearly half of all pregnant women experience iron deficiency, contributing to high maternal mortality rates.

Access to safe drinking water exists for approximately 78% of the population, but this figure applies mostly to urban areas. In rural regions, people rely on wells and streams often contaminated with sewage and pathogens. During the rainy season, this leads to frequent outbreaks of dysentery, cholera, and typhoid fever.

Crime remains one of the country’s most acute problems. The government has failed to assert control over organized crime, leaving criminal gangs in command of the streets. Their primary activities include human trafficking and tobacco smuggling, often accompanied by violent turf wars. Moreover, some political parties reportedly employ gang members to intimidate opponents, blurring the line between politics and crime.

Papua New Guinea (Oceania)

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is one of the most dangerous and contradictory countries in the world. The nation possesses large reserves of natural resources such as gold, copper, oil, and gas, but the government has limited control over its territory. Corruption, tribal loyalties, and local armed groups have seriously weakened the central authority, creating a fragmented and unstable state.

In the capital city of Port Moresby, the homicide rate reaches up to 120 murders per 100,000 inhabitants each year, which is among the highest figures globally. In Morobe and Eastern Highlands provinces, intertribal conflicts result in dozens of deaths annually. Urban areas are affected by the phenomenon of «raskol gangs,» armed street groups involved in extortion, kidnappings, attacks on tourists, and robberies of cargo trucks.

The police force is poorly funded and severely undermanned. With only 75 officers per 100,000 people, it cannot effectively counter organized violence. Lawlessness is often accompanied by sexual violence. According to UN estimates, 67% of women in Papua New Guinea have experienced physical or sexual abuse at least once in their lives.

The healthcare system is one of the weakest in the Pacific region, and life expectancy does not exceed 56 years. Malaria remains a major health concern, with about one million cases every year. In the southern rural areas, there are also chloroquine-resistant strains of the disease.

Other serious health problems are common as well:

- Tuberculosis (TB): about 430 cases per 100,000 people, one of the highest rates in the region, with an increasing number of multidrug-resistant forms.

- HIV/AIDS: around 60,000 people are infected, or about 0.6% of the adult population, which is the highest prevalence rate in Oceania and continues to grow.

- Leprosy and measles are still recorded every year.

The country faces a chronic shortage of both medical facilities and doctors. In 2025, there are only 0.7 doctors per 10,000 inhabitants. The situation is worsened by the lack of medicines and vaccines.

Papua New Guinea is located on the Pacific «Ring of Fire,» where earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, landslides, and floods occur frequently. These disasters often destroy infrastructure and threaten entire communities.

A distinctive feature of PNG’s social reality is the persistence of cannibalism-related practices. Historically, the country was among the last places on Earth where ritual cannibalism existed as part of cultural tradition. Although it has been officially eradicated, isolated cases are still reported today.

Since 1971, the country has maintained a Sorcery Act, which states that a person who believes themself to be bewitched is not fully responsible for a crime committed under such influence. This law is also used as a mitigating circumstance for defendants if their victim is considered a sorcerer.

One of the most infamous incidents occurred during the 2012 general elections, when a group of so-called «witch hunters» murdered several people, burning them alive in front of relatives and consuming the remains under the pretext of fighting witchcraft.

Summary

There are other countries where life is made difficult not only by war but also by chronic problems such as epidemics, poverty, lack of clean water, and corruption. The Solomon Islands suffer from frequent hurricanes, Honduras faces the dominance of violent gangs, Bangladesh struggles with flooding and overpopulation, and the Central African Republic is plagued by hunger and parasites. Yet the situation in these places remains somewhat better than in the countries discussed above.

Living in such states is extremely difficult, and they should not be considered suitable destinations even for short-term stays. Nevertheless, people continue to live there, adapting to harsh conditions when they have no other choice and migration is not an option.

Author

I write informative articles about real estate, investments, job opportunities, taxes, etc.